A new study funded by the Emily Ann Hayes Research Fund within Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center looks into racial disparities within the Down syndrome community.

Six researchers conducted a detailed study looking at pre- and post- natal complications and existing co-occurring medical conditions hoping to find answers about why Black children with Down syndrome have a higher mortality rate than White children.

The report, in press at The Journal of Pediatrics, begins with an outline of what is known from previous research including the following:

- The life expectancy of people with Down syndrome has increased drastically in the last several decades but no one factor fully explains the reason why – early identification and treatment of congenital heart defects has contributed significantly but is not the only factor.

- Compared with White mothers, Black mothers are “younger and more likely to be at a lower socioeconomic level” but studies have not linked these factors to mortality.

- “Although some degree of difference in life expectancy by race is seen among the US population as a whole, the magnitude of this racial disparity is larger in the Down syndrome population.”

The researchers designed the study to look at:

- Medical conditions of the mother before birth

- Medial issues of the child

- Referrals to other doctors as a gauge of access to care

- National death record databases

Data was collected between 1984 and 2009 from patients at the Down syndrome clinic within the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

The number of factors investigated is impressive.

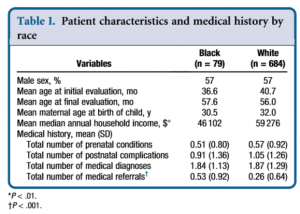

Children with Mosaic Down syndrome and those of races other than Black and Caucasian were not included because of the small number of participants of these groups available for this study. The final number of participants was 763.

No significant difference was found for prenatal risk factors, postnatal birth complications or total number of medical conditions.

There was a significant difference in the number of referrals made. Researchers suspect that difference in numbers of referrals may have something to do with access to care. They suggest that this is an area where further research is necessary and indicate that future researchers should also look at the type of primary care physician used and no-show rates.

When discussing the issue of congenital heart defects (CHD) the researchers note that improvements in care have contributed substantially to the increased lifespan of White people with Down syndrome and CHD but not for Blacks with Down syndrome and CHD. They question whether Black children received echocardiograms prior to their visit at the Down syndrome clinic. Baseline echocardiograms are recommended for all children with Down syndrome.

A portion of the study looked at death records. All of the participants were under age 21 when the study started in 1984. By the end of the study, 2009, 26 participants were deceased. Of the 79 Black subjects in the study, 7 were deceased. 17 of the 684 White subjects were deceased. The number of people who died during the study was significantly higher for Blacks, but there was no statistically significant difference by race in the age at which participants died.

When looking at the death records, two important issues were identified. The first being that 25% of the death records listed “Down syndrome unspecified” as the primary cause of death. We all know that Down syndrome does not cause anyone to die. This does reinforce the need for better understanding and reporting on death certificates.

The other unanticipated find was the high number of deaths caused by infection.

The Bottom Line

Final outcomes of the study suggest that, at least for those in the study, the causes for the racial health disparity was not medical.

“We investigated dozens of factors in an effort to detect even subtle differences between the Black and White subjects with Down syndrome, but found few. We found no medical basis for racial disparity in life expectancy.”

The final paragraphs of the report are dedicated to the limitations of the study. Every study has them. In this case, one of the issues to consider is that all of the participants had access to a Down syndrome clinic. Another limitation mentioned by the researchers was the possible inaccuracy of the death records.

“The underlying cause for the racial disparities in health care remains elusive and if discovered could help improve care for the increasing number of adults with Down syndrome of all races.”

While it’s encouraging to see that another study has been completed, we still have a long way to go until we fully understand what is going on here. Research builds on past results. Each new study adds a piece of the puzzle. We can never know how many pieces are in each puzzle until it’s complete.

What we do know is that we need more pieces.

*Special thanks to Dr. Michael Harpold, Chief Scientific Officer of the LuMind Research Down Syndrome Foundation, for bringing this article to our attention.